Introduction

We are fortunate to live in a time not only of great

discoveries and advancements in the field of exoplanet science,

but to live in a time when the most cutting-edge data for

studying these planets is freely available for anyone to

download off the internet. This webpage is designed to give an introduction to how we find planets using the "transit method," one of the most common methods for detecting exoplanets today, and the method used by the Kepler space telescope. This tutorial will then teach the reader how to download Kepler data (in particular data from Kepler's second mission called K2), look for planets in it, and learn the planetary properties using tools available in any modern web browser.

We are fortunate to live in a time not only of great

discoveries and advancements in the field of exoplanet science,

but to live in a time when the most cutting-edge data for

studying these planets is freely available for anyone to

download off the internet. This webpage is designed to give an introduction to how we find planets using the "transit method," one of the most common methods for detecting exoplanets today, and the method used by the Kepler space telescope. This tutorial will then teach the reader how to download Kepler data (in particular data from Kepler's second mission called K2), look for planets in it, and learn the planetary properties using tools available in any modern web browser.

What are exoplanets?

Exoplanets are planets, much like the ones in our Solar system, that we have discovered orbiting stars other than our Sun. The first exoplanets were found in the late 20th century (in 1989, 1992, or 1995, depending on one's definition of an exoplanet), and since then we have discovered thousands of these worlds orbiting other stars in the galaxy. While many exoplanets mirror the planets we know of in our own Solar System, many others are hard to recognize - including giant exoplanets orbiting extremely close to their host stars (called Hot Jupiters) to planets larger than Earth, smaller than Neptune, and likely rich in volatile materials (called super-Earths or mini-Neptunes), and planets which instead of orbiting one host star are found around two very closely orbiting stars (called circumbinary planets).

What are transiting exoplanets?

Astronomers have several methods at our disposal to detect exoplanets. Historically, many of the first exoplanets to be discovered were found via the radial velocity method. Using super-precise and ultra-well calibrated instruments, astronomers searched for the tiny wobble in the star's speed caused by the planet's orbit. Other methods at exoplanet astronomers' disposals include detecting gravitational lensing due to a planet (called the microlensing method), searching for the wobble in the star's position on the sky (called the astrometric method), and separating the light of the star from the planet and actually taking images (called the direct imaging method).

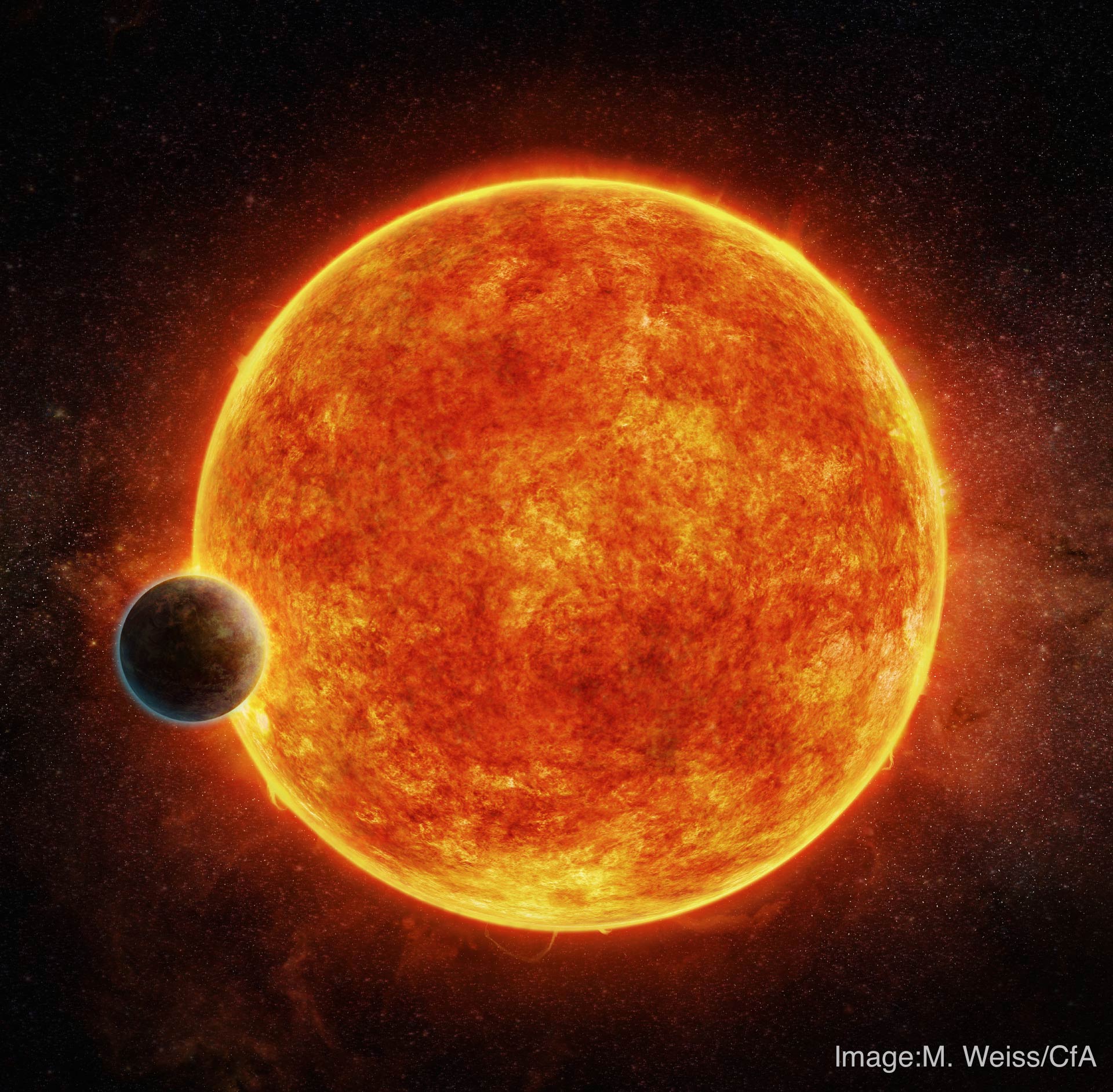

This tutorial focuses on the transit method, where we search for the periodic dimming of light as an exoplanet passes in front of its host star and casts its shadow on our telescopes. An animation below illustrates what happens when a planet transits:

Animation credit: NASA

In this animation, the green line being drawn below the planet and star is called the "light curve." The light curve is a graph of the brightness of the star over time, and is the measurement Kepler makes to discover exoplanets. The dip in light that happens when the planet passes in front of the star is called the "transit." Transits give information about the planet's size and orbit. The animation below shows a planet transiting three times successively before the transits are detected by Kepler:

Animation credit: NASA

The length of time between each transit is the planet's "orbital period", or the length of a year on that particular planet. Not all planets have years as long as a year on the Earth! Some planets discovered by Kepler orbit around their stars so quickly that their years only last about four hours!

Perhaps the most important fact about transiting planets is that we can measure the planet's size. This measurement is extremely difficult to make if the planet does not happen to transit. The amount of light a planet blocks in transit depends on the size of the planet. A large planet blocks more light than a small planet, so the large planet will have a deeper transit. This is illustrated in the animation below:

Animation credit: NASA

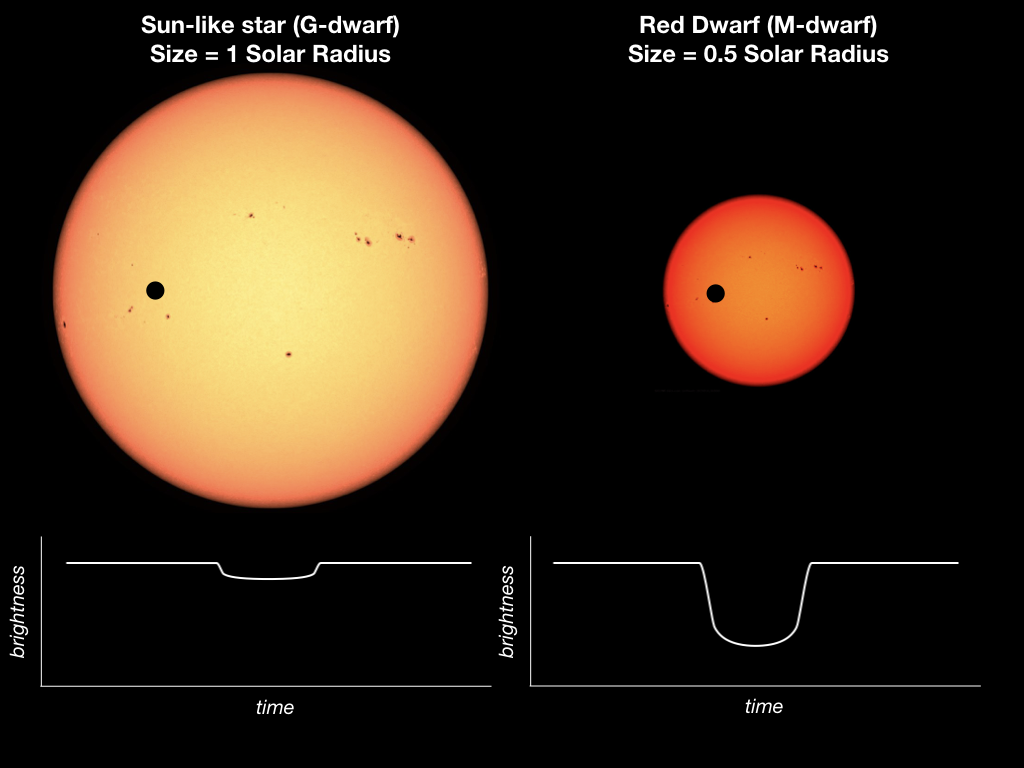

Measuring the transit depth is not enough to measure the size of the planet - you also need to know the size of the star it is transiting. The image below illustrates how a planet transiting a small star (on the right) causes a larger transit signal than the same sized planet transiting a large star on the left:

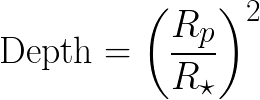

Specifically, the transit depth is equal to the ratio between the planet's radius (Rp) and the star's radius (R*) squared:

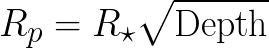

Meaning that the planet's radius can be found using the following formula:

Click the link to continue onto Page 2.

Originally written April 2017, updated July 2021.